Latest News & Promos

- Details

- Written by The Community Eyecare Team

It is safe to say that many people prefer shopping online to shopping in stores for many of their needs.

With technology constantly improving and evolving, people tend to take advantage of the convenience of shopping online. Whether it’s clothing, electronics, or even food, you can easily find almost everything you need on the Internet.

Eyeglasses, unfortunately, are no different. Many online shops have been popping up in recent years, offering people that same convenience. But what...

- Details

- Written by The Community Eyecare Team

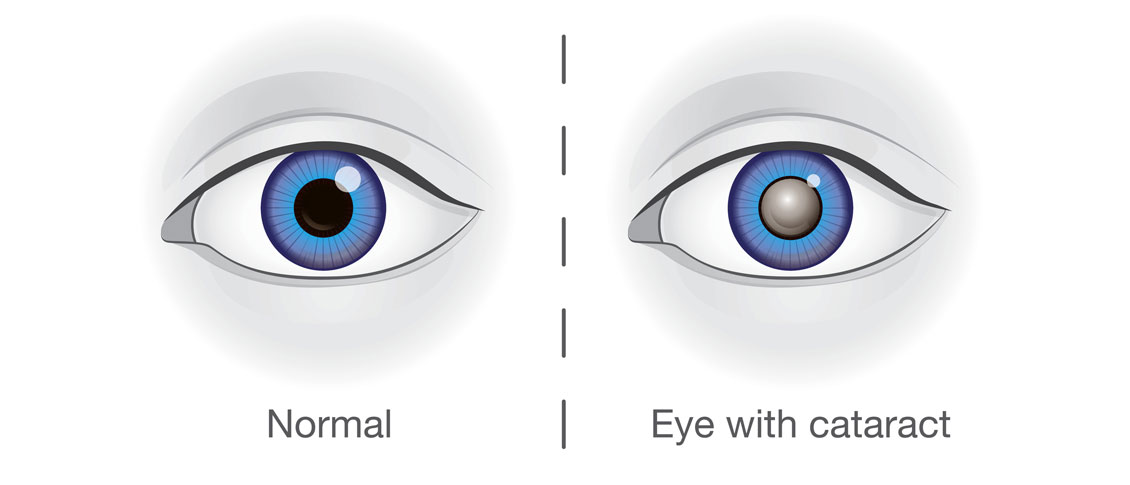

You’ve been diagnosed with a cataract and you’ve been told you should have cataract surgery. The surgeon is also telling you that you should consider paying extra out of pocket it for it.

Where did this come from? Why should you have to pay out of pocket for cataract surgery? Shouldn’t your health insurance just cover it?

In trying to answer those questions, you will first need a little history of both cataract and refractive (correcting errors of refraction such as nearsightedness,...

Patient Resources

Please Leave a Google Review

We sincerely appreciate our patients and welcome your feedback. Please take a moment to let us know how your experience has been.

Our Dry Eye Center

Northeast Wisconsin's Optometrists of Choice

Menasha Office

1255 Appleton Road

Menasha, WI 54952-1501

Phone: (920) 722-6872

CALL 1ST - NO WALK-INS

Brillion Office

950 West Ryan Street

Brillion, WI 54110-1042

Phone: (920) 756-2020

CALL 1ST - NO WALK-INS

Black Creek Office

413 South Main Street

Black Creek, WI 54106-9501

Phone: (920) 984-3937

CALL 1ST - NO WALK-INS

© Community Eyecare, Inc.: 3 Convenient Northeast Wisconsin Locations | Menasha, WI | Brillion, WI | Black Creek, WI | Site Map

Text and photos provided are the property of EyeMotion and cannot be duplicated or moved.